Fred Wertheimer in New Yorker – “The Money Midterms: A Scandal in Slow Motion”

The New Yorker – The Money Midterms: A Scandal in Slow Motion

By: Evan Osnos

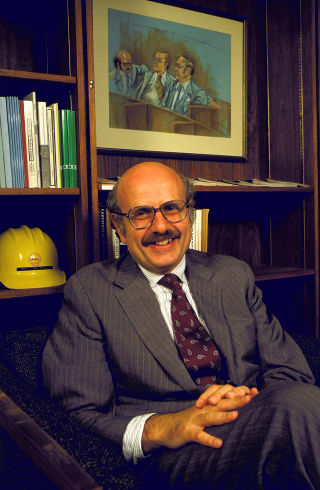

In 1971, after studying law at Harvard, Fred Wertheimer became the chief lobbyist for Common Cause, a non-profit that aimed to limit the corrosive influence of money in politics. He was thirty-two years old. “Watergate comes along the next year, we pass Presidential public financing, we almost pass it for congressional races, and I say to myself, ‘This is pretty easy,’ ” Wertheimer told me recently.

He took it as a sign of progress when, on October 15, 1974, Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act amendments, part of a series of reforms that restricted campaign donations and imposed spending limits. Their intent was to reduce corruption. At the time, he said that he thought, “By the end of the seventies, we’ll have congressional public financing, and I can find something else to do.” But, in 1976, the Supreme Court blocked parts of the post-Watergate reforms, ruling on First Amendment grounds, and the Court has steadily pared away the limits on campaign spending ever since—most significantly in 2010, when the majority decision in Citizens United threw out restrictions on the amounts that corporations, individuals, and unions could spend in independent efforts to shape elections.

Forty years after the passage of those post-Watergate reforms, the elections on November 4th are on pace to be the most expensive midterms in history (even adjusting for inflation), a distinction hardly worth mentioning in an era when each cycle sets a new record of one kind or another. The last midterm elections, in 2010, cost $4 billion; the 2012 Presidential race added up to $6.3 billion. The spending in this year’s race, however, is distinguished by scale and secrecy: “dark money”—the cash from non-profits that aren’t required to disclose the names of their donors—now represents more than half of all spending by outside groups in the year’s most competitive Senate races, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. These groups have spent more than a hundred million dollars in this cycle, more than in any previous midterm election, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. (That’s a fraction of the total; much of their spending won’t show up in disclosure reports for months.) In Kentucky, for example, a group calling itself the Kentucky Opportunity Coalition has spent fourteen million dollars to support Republican Senator Mitch McConnell’s campaign and to label his opponent, Alison Lundergan Grimes, as the instrument of “anti-coal” forces. The source of the money is unknown.

Republicans have been the beneficiaries of most of this cycle’s dark money, but Democrats have proved to be enthusiastic recipients of money from super PACs, the independent political-action committees that can can spend unlimited funds but that have to declare their donors. (To keep their right to secrecy, dark-money groups can’t spend more than half of their funds on politics.) This week, NextGen Climate Action Committee, a progressive super PAC founded by Tom Steyer, a hedge-fund founder, reported that his most recent donations have pushed his contributions to a total of fifty-five million dollars, a sum that surpasses the $49.8 million that the casino magnate Sheldon Adelson gave to super PACs in the 2012 election.

Will anything stop those sums from growing again in two years, and two years after that? I live in Washington, so I am supposed to say no. A heat map of conversations in our nation’s capital this week would show that campaign-finance reform is generating about as much urgent attention as the disappearance of the honeybee. If the reflexive talking point in San Francisco is to bet on disruption, the conventional line in Washington is that the forces arrayed against change are the stronger ones.

And, yet, it’s hard not to sense that a combination of forces is making change, of some kind, unavoidable. At a moment when Americans are divided along party lines, they are united in their abject loathing of the United States Congress, which is on track this year to pass fewer laws than any Congress in history. In a Gallup poll, seven per cent of Americans reported having confidence in Congress, the lowest level that Gallup has ever recorded for any institution. Most Americans have a negative view of both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, and the share of independents continues to rise, reaching forty-four percent in September. Ron Fournier, writing this week in National Journal, predicted that incumbents will generally survive this fall, which will create a false sense of calm. “The Old Guard will conclude that the status quo is safe. But the Old Guard is a ship of fools, living on borrowed time,” he wrote. “They remind me of smug newspaper publishers, music moguls, and bookstore-chain operators who were abruptly disrupted out of business.”

Four decades after Fred Wertheimer got into the business of campaign-finance reform, he would be entitled to be cynical about the likelihood of meaningful changes. He has seen the illusion of progress so many times; after the passage of one campaign-finance bill, a Washington Post reporter described Wertheimer as looking forward to “more time for racquetball, jogging and indulging his fondness for rock-and-roll.” That story ran twelve years ago, and Wertheimer is still at it. (In 1997, after twenty-four years at Common Cause, he started Democracy 21, a nonprofit advocacy group.)

And yet Wertheimer told me this fall that he smells a storm coming. He said, “The world changes on this issue when you get scandals”—the political pratfalls that leave lawmakers no choice but to enact new protections. “What is going on now is a national scandal, but it doesn’t have the concrete examples that have occurred in the past. It doesn’t have Jack Abramoff”—the disgraced lobbyist who hastened a round of ethics reforms. “We have three elements today: unlimited contributions, corporate money, and secret money. Those were the three elements of the Watergate campaign-finance scandal,” Wertheimer said. “They’re back.”